In a world where waste is a growing issue and energy demand is rising, waste to energy solutions have emerged as a promising approach.

And an increasing number of companies are joining this movement.

If you’re interested in converting diverse organic waste streams into energy, you’ve likely noticed this is no small task. And while it comes with several considerations for successful implementation, it’s not impossible, especially with the right guidance.

This comprehensive guide walks you through everything you need to know, with a strong focus on pre-treatment, risk, compliance, and pathway selection.

Key Takeaways

- Waste to energy is an umbrella term, and confusing mass-burn incineration with organic waste to energy can lead to weaker project outcomes.

- Food waste is only one part of the opportunity, as agricultural residues, industrial byproducts, and wastewater residuals often provide consistent and reliable feedstocks for organic waste to energy systems.

- Pre-treatment is the foundation of waste to energy success, as contamination removal, feedstock conditioning, and uniformity directly determine system performance, regulatory compliance, and project economics.

- Choosing between waste to energy, composting, or disposal depends on waste characteristics, regulatory pressures, and operational goals, with integrated models often providing the most flexibility and resilience.

What “Waste to Energy” Means in the Context of Organic Waste

In the context of organic waste, waste to energy (WtE) means converting materials like food scraps and agricultural residues into usable energy. Through a controlled waste to energy process, organic waste can be diverted from landfills and converted into electricity, heat, or fuel, thereby supporting more sustainable energy production.

Waste to Energy vs. Traditional Waste Disposal

This approach differs from traditional waste disposal methods, such as sending waste to landfills, which simply store waste rather than recovering value from it.

It’s also important to note that “waste to energy” is an umbrella term used to describe various processes and technologies, and mixing them up can lead to poor decisions and weaker project outcomes.

While the most common waste to energy system in the U.S. is mass burn, which incinerates unprocessed MSW, turning organic waste to energy offers a cleaner, more targeted alternative.

For that reason, this article doesn’t focus on the broad subject of waste to energy, but rather on how it applies to organic waste.

Organic Waste Streams Suitable for Energy Conversion (Beyond Food Waste)

Food waste is estimated at between 30% and 40% of the food supply in the United States, meaning it offers a huge opportunity for generating energy. That said, turning food waste to energy is just one organic waste stream among many.

The others include:

1. Agricultural and Livestock Residues

Agriculture and livestock residues include manure, bedding, crop residues, and more. In addition to producing sustainable energy, they help farms address complex waste management challenges.

To put that potential into perspective, a study found that available surplus crop residue can fulfill 100% of the cooking energy demands of rural India, while livestock waste could fulfill 37%.

That said, consistency and volume matter more than energy density because waste to energy systems depend on a steady, predictable feedstock supply to operate efficiently.

2. Industrial Organic Byproducts

Industrial organic byproducts are secondary materials generated during manufacturing processes. This includes a range of materials, such as food and beverage processing waste, fats, oils, and grease, as well as dairy byproducts, brewery and distillery waste, and other organic residues that would otherwise require costly disposal.

In many cases, industrial streams outperform municipal food waste in stability because they’re more consistent in composition, cleaner, and generated at predictable volumes.

3. Biosolids and Wastewater Residuals

Biosolids and wastewater residuals include organic materials like primary sludge, waste-activated sludge, and other solids removed during wastewater treatment. While these streams are often viewed as a disposal challenge, sludge can also serve as a reliable energy source when processed through the right waste to energy pathway.

Co-processing is common because wastewater residuals tend to have high moisture content and variable characteristics, so blending them with other organic inputs can improve digestion performance, stabilize operations, and increase overall energy output.

According to ScienceDirect, “Factors such as a hike in fuel prices, depletion of non-renewable energy, climate change, and public awareness, have motivated the research community to intensify research on the application of sewage sludge as a valuable source of renewable energy.”

The Hidden First Step — Pre-Treatment and Feedstock Conditioning

Pre-treatment should never be an afterthought. To fully realize waste to energy benefits, it should be the first step.

Here’s why:

1. Contamination Removal and De-Packaging

Various materials must be removed to prevent contamination, including plastics, metals, and other inert materials. Depackaging systems play a critical role in separating organic waste from packaging by filtering out organics from plastics, metals, and other contaminants.

Because contamination tolerance ultimately defines facility acceptance, effective removal upfront helps ensure the feedstock meets strict processing requirements.

In addition to protecting waste to energy technologies, contamination removal also supports higher energy output and improved environmental compliance, making it a key first step in the process.

2. Size Reduction, Homogenization, and Moisture Control

Feedstock inconsistency can reduce operational stability and lower overall yield. For that reason, maintaining uniformity is critical.

For example, one study found that using a specially modified low-pressure homogenizer to break down sludge produced about 30% more methane energy than untreated sludge.

This shows how pre-processing steps like size reduction and homogenization can create a more consistent, digestible feedstock, helping reduce disruptions caused by uneven moisture levels or particle size.

3. Why Pre-Treatment Determines Project Economics

Pre-treatment plays a major role in determining whether a project is profitable because it directly affects the balance between energy output and ongoing operating costs. However, while pre-processing can increase biogas yields and improve system stability, it also adds equipment, labor, and maintenance expenses that must be justified by the performance gains.

And even when a feedstock looks inexpensive upfront, it can become costly if it requires extensive handling, moisture adjustment, or contamination removal.

By working with a waste management partner like Shapiro, you can optimize feedstock quality and consistency from the start, helping improve cost efficiency. Contact us today to discuss our custom solutions.

Organic Waste to Energy Pathways — Choosing the Right Conversion Route

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to choosing the right organic waste management strategy. Companies can consider anaerobic digestion, thermochemical options, or even a hybrid approach.

1. Anaerobic Digestion as a Biological Pathway

If you’re familiar with how anaerobic digester systems work, then you already know they’re a powerful way to convert organic waste into biogas and nutrient-rich fertilizer. And while anaerobic digestion is gaining momentum worldwide, one factor consistently determines how well the process performs: feedstock quality.

When feedstock quality fluctuates, the microbial community inside the digester can’t maintain a stable balance, leading to inefficiencies and overall performance drops.

For that reason, maintaining consistent, high-quality inputs is essential for maximizing biogas yield and keeping operations reliable.

2. Thermochemical Options for Organic Fractions

Several waste to energy technologies fall under the thermochemical category, including:

- Waste gasification, which converts waste materials into a combustible gas mixture through partial oxidation at high temperatures, allowing for energy recovery and potential chemical production.

- Pyrolysis, which allows for the thermal decomposition of waste in the absence of oxygen, making it a promising method for converting waste into usable energy.

When deciding between thermochemical options and other solutions like anaerobic digestion, several factors should be considered, including the moisture content of the organic waste, the desired end product, and the scale of operation.

Hybrid and Integrated Systems

Sometimes, waste to energy plants combine different technologies and processes to maximize efficiency and manage diverse waste streams.

For example, co-digestion can boost biogas output by blending complementary feedstocks, while pre-treatment can prepare organics for multiple recovery paths, such as anaerobic digestion or thermochemical conversion, based on what delivers the best return.

At Shapiro, we review your unique waste stream to determine the best recovery path—so you can maximize value, reduce risk, and choose the solution that fits your goals.

Feedstock Stability and Process Risk (Why Projects Fail)

The harsh reality is that not all sustainability initiatives succeed. Without a deep understanding of how waste to energy works, or working with someone who does, operational missteps can occur and impact long-term performance, reliability, and ROI.

1. Variability, Shock Loads, and Inhibitors

Even the best-designed systems can struggle when feedstock quality shifts too often or too drastically.

Seasonal variation and sudden “shock loads” can disrupt the biological balance, while high acidity, fats, and inhibitory compounds can slow microbial activity. This can lead to reduced output, operational instability, and costly downtime.

2. Co-Digestion as a Risk-Management Strategy

Co-digestion helps reduce risk by blending multiple waste streams to create a more consistent, predictable feedstock. And while beneficial in some circumstances, it can also introduce new challenges. Why?

Because it adds complexity, requiring tighter monitoring, careful ratio control, and stronger operational planning to avoid unintended process issues.

3. Monitoring, Control, and Operational Oversight

A bigger system doesn’t automatically mean a more reliable one.

In anaerobic digestion, for instance, consistent performance depends less on digester size and more on how well the process is monitored and controlled. With the right automation and oversight, operators can spot instability early, adjust inputs quickly, and prevent small issues from turning into costly shutdowns.

Energy Outputs — What You Actually Get from Organic WtE

Here’s a quick look at the energy you can get from organic waste to energy systems.

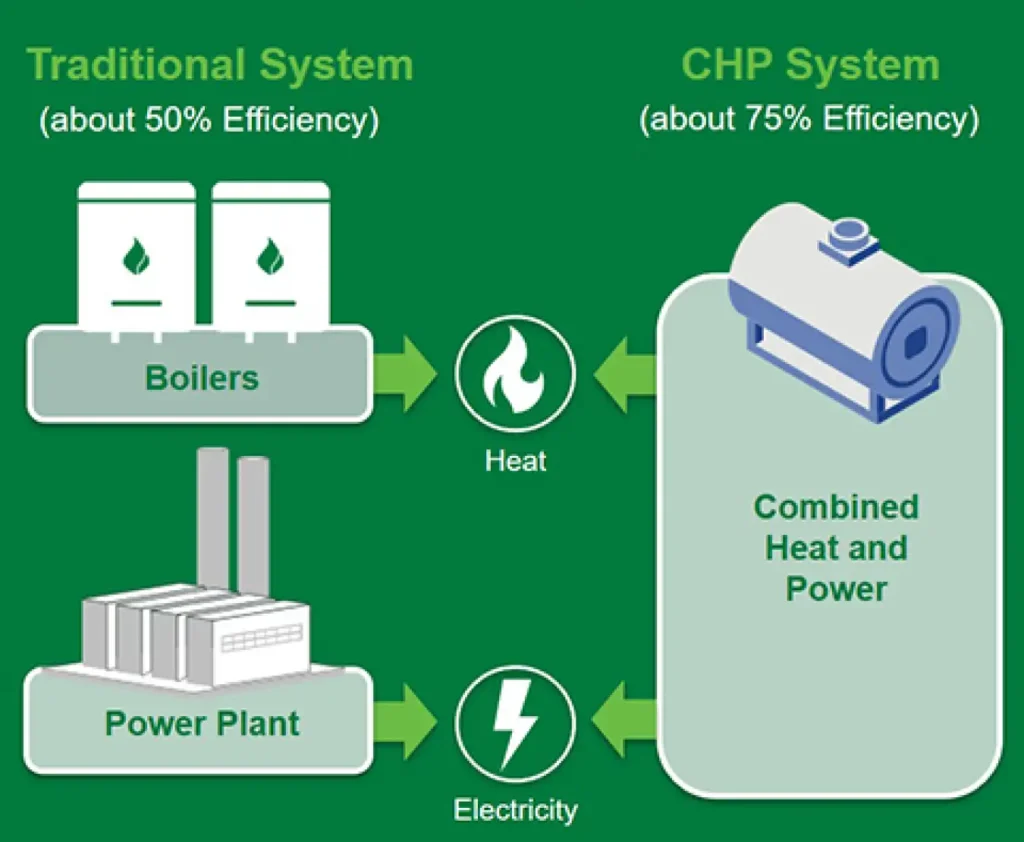

1. Electricity and Heat (CHP Context)

CHP, or combined heat and power, can run on a variety of fuels and has been employed for many years, mostly in industrial, large commercial, and institutional applications.

With on-site power production, losses are minimized, and heat that would otherwise be wasted is applied to facility loads in the form of process heating, steam, hot water, or even chilled water. It typically makes the most sense when a facility has steady, year-round demand for both electricity and thermal energy.

For example, in anaerobic digestion projects, CHP can support biogas electricity generation by converting biogas into electricity and usable heat.

Biogas vs. Biomethane vs. Grid Injection

Not all projects produce the same output, and the right path depends on how you plan to use (or sell) the energy.

- Biogas: Biogas from organic waste is produced through anaerobic digestion and is typically used on-site for heat, electricity, or CHP. One of the key advantages of biogas is that it enables renewable energy recovery directly at the source.

- Biomethane: Biomethane is biogas that’s been upgraded to remove impurities and boost methane content, making it suitable for higher-value uses like vehicle fuel or pipeline-quality gas.

- Grid injection: Grid injection involves conditioning biomethane to meet utility standards so it can be injected into the natural gas network, which can be a strong option when on-site energy demand is limited.

2. Matching Output Type to End-User Needs

Your company must also evaluate how it plans to use anaerobic digestion energy.

Common options include:

- Industrial facilities: Industrial facilities often prioritize consistent heat and power to support energy-intensive operations and reduce utility costs.

- Municipal projects: Municipal projects typically focus on scalable, community-wide solutions that can manage diverse waste streams and support local infrastructure.

- On-site consumption: On-site consumption works best when there’s steady, predictable demand, so the facility can capture the full value of the energy produced.

Digestate — Resource, Liability, or Revenue Stream?

Digestate is often positioned as a valuable waste management solution, but under certain conditions, it can become a liability:

1. When Digestate Is a Liability

While digestate offers clear benefits, it also carries potential risks that shouldn’t be overlooked. In certain conditions, digestate can be considered hazardous, particularly when it’s poorly managed or improperly stored.

A generic risk assessment of anaerobic digestion highlights several key concerns. Groundwater can be threatened by leaks or spills from digestate tanks and storage vessels. In addition, digestate and its storage systems can release ammonia, which can significantly degrade air quality. The combustion of biogas or biomethane may also generate harmful pollutants if not properly controlled.

For instance, research has shown that pig slurry digestate can be highly toxic and associated with elevated environmental risk. As a result, pre-treatment is often required to reduce its toxicity before land application or disposal.

2. Regulatory and Compliance Considerations

Anaerobic digesters must meet local, state, and federal regulatory and permitting requirements for air, solid waste, and water. These requirements typically involve obtaining environmental permits and adhering to operational standards designed to protect human health and the environment.

To ensure that land application is properly done, a nutrient and soil management plan is required in most states. These plans reduce the risk of nutrient runoff or groundwater contamination and ensure compliance with water quality protection laws.

3. When Digestate Adds Value — and When It Doesn’t

Digestate is a nutrient-rich fertilizer that can enhance soil health, increase crop yields, and support more sustainable agricultural practices. In some cases, digestate-derived fertilizers can be certified as an organic product, which may significantly increase their market value and create an additional revenue stream.

However, digestate does not always deliver economic value.

Limited market access can reduce demand, particularly in regions without nearby agricultural users or established distribution channels. Transportation and storage challenges can further erode profitability, as digestate is often high in moisture and costly to move over long distances.

When handling, storage, or application costs outweigh local demand or nutrient value, digestate may offer minimal financial return and function primarily as a waste management solution rather than a revenue-generating product.

Waste to Energy vs. Composting vs. Disposal — A Decision Framework

Determining the most appropriate waste management approach requires evaluating waste characteristics, operational capacity, regulatory constraints, and recovery objectives. The following framework outlines when each approach delivers the strongest outcomes:

1. When Organic Waste to Energy Is the Better Option

Organic waste to energy is often the better choice for high-moisture, high-volume waste streams where transporting or land-applying digestate is impractical or costly. In these cases, converting waste into energy maximizes value while reducing handling and disposal challenges.

Waste to energy can also be driven by regulatory pressures, such as landfill diversion mandates or restrictions on land application. These factors can make energy recovery a more reliable and compliant solution.

2. When Composting or Other Methods Are Preferable

Composting or alternative treatment methods may be preferable when organic waste streams are low in contamination and well-suited for direct soil applications.

In these cases, the primary goal is often improving soil health rather than maximizing energy recovery. For operations focused on soil quality, carbon sequestration, or local nutrient cycling, composting can deliver clearer environmental and agronomic benefits.

3. Integrated Waste Management Models

Advanced waste management systems increasingly rely on multiple treatment pathways rather than a single solution.

By combining approaches such as anaerobic digestion, waste to energy, and composting, organizations can adapt to varying waste streams, regulatory requirements, and market conditions. This integrated model improves flexibility, resilience, and overall resource efficiency.

Organizations often achieve the best results by combining multiple treatment approaches rather than relying on a single pathway. Shapiro evaluates your unique waste stream characteristics and helps identify the most effective approach, whether that’s a single pathway or an integrated combination. Contact us to discuss your specific requirements.

Environmental Impact — Benefits with Conditions

The environmental performance of organic waste treatment systems depends on design, operation, and oversight. While these systems can reduce environmental impacts compared to uncontrolled disposal, the benefits are conditional rather than automatic.

1. Emissions Reduction Depends on System Design

Effective methane capture is essential to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Systems that efficiently collect and utilize biogas from organic waste can prevent methane from escaping into the atmosphere.

However, leakage during digestion, storage, or energy conversion can significantly reduce or negate these emissions benefits.

2. Circular Economy Alignment (Without Buzzwords)

Organic waste treatment can support circular resource use by recovering both energy and nutrients. Where digestate or recovered energy can be productively used, these systems contribute to material efficiency.

However, their role within the waste hierarchy depends on context, and energy recovery does not replace higher-value material recovery options when those outcomes are achievable.

Is Organic Waste to Energy the Right Solution?

Determining whether organic waste to energy is appropriate requires evaluating several practical factors. These include the characteristics of the waste stream, operational capacity, regulatory requirements, and the ability to use or sell recovered energy.

When these conditions align, organic waste to energy can deliver meaningful benefits. When they do not, it can be inefficient or environmentally neutral at best.

Shapiro brings experience across a wide range of waste types and management pathways, helping companies identify the solution that delivers the greatest impact. We develop tailored strategies and manage the process end to end.

Contact us today to learn more.

FAQs about Waste to Energy

No. Waste to energy is an umbrella term that includes multiple technologies, while organic waste to energy recovers energy from organic materials without combusting the waste through incineration.

Organic waste with high contamination, low biodegradability, or inconsistent composition can limit system performance and increase operational risk.

Many projects fail due to inadequate pre-treatment, variable or contaminated feedstock, and challenges managing digestate.

Effective sorting, de-packaging, and homogenization improve system stability, reduce downtime, and directly influence long-term operating costs.

No. The appropriate approach depends on waste characteristics, regulatory requirements, and whether there is a clear and consistent demand for recovered energy.

Digestate is a regulated output that requires quality control, appropriate handling, and access to end-use markets, making it a key planning consideration rather than an assumed benefit.

Yes, but success depends on system design, contamination control, and the ability to manage variability across different waste inputs.

Permitting, environmental compliance, and ongoing reporting requirements play a central role in feasibility, and regulatory readiness often determines whether a project can move forward.

Baily Ramsey, an accomplished marketing specialist, brings a unique blend of anthropological insight and marketing finesse to the digital landscape. Specializing in educational content creation, she creates content for various industries, with a particular interest in environmental initiatives.